Music subcultures: Theoretical view

Music is considered by many to be the highest form of art and culture. Music is also considered by many to epitomise their values and tastes, as well as those of other people. Music is very often a product of its time – both a reflection of the ‘here and now’ and a ‘recaller’ of memories. Music and youth are usually deemed to hold a special relationship with each other. Music is delivered and sold to youth audiences, and young people on the whole are fans of one music genre or another.

Informed by wider theoretical developments in the sociology of consumption and everyday life as well as cultural and media studies, but there are researches that is less interested in how young people are located within music structures than in how music interacts with the structures of their everyday lives. Classic structuralist accounts of youth subcultures (e.g. Clarke and Jefferson 1973; Willis 1978) have tended to locate music alongside other artefacts within an all-embracing style as homology. In the case of punks, for example, a preference for heavy rock music was not understood in relation to everyday education, work and leisure contexts, but solely in relation to syntagmatic leisure contexts in which the punk style – heavy rock, outlandish hairstyles, leather boots and jackets, safety pins and homemade clothes – was collectively lived out. Some studies, in stark contrast, intends to situate music in relation to the various leisure and non-leisure contexts recurrent in young people’s lives. Music is not presumed to fit into spectacular systems of signification that are opposed to dominant social and cultural forces but is instead situated in the localised interactions that typify the ordinary, routine and mundane circumstances of young people’s everyday experiences.

Much early work around youth subculture and music started with the music and applied it – often without sound empirical evidence – to a given subculture or generation. However, there are important exceptions to this rule. A strand of thinking about youth culture and music from the perspective of those characterised by the former concept can be traced back to a pioneering analysis of ‘youth culture’ as a social entity (Parsons 1942). Following in this tradition, Mungham (1976), Murdock and McCron (1976) and Frith (1978; 1983; 1986) were among the first youth sociologists who both worked alongside exponents of a youth cultural studies tradition but at the same time redressed the lack of empirical insights that had thus far informed an understanding of youth music subcultures.

Whilst semiotic or historical readings of youth subcultures have suggested quite uncritically the working-class position of youth subcultures, more rigorous sociological research has demonstrated the complexity of social class, given that a typical lengthening of the transitional phase among more affluent young people has led to greater parity in levels of disposable income experienced by youth of all social classes. Situating music in juxtaposition with the everyday transitions of (sub)cultures is also helpful in order to understand how the process of growing up can correspond to changing contexts of leisure. Theories of subculture have tended to assume that public contexts free from parental controls accommodate the spaces for youth musical expression.

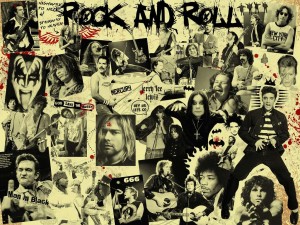

Music subcultures: Rock, pop and fan subcultures

If histories of youth subcultures invariably begin with the Teddy Boys, histories of rock and pop music often cast their anchor similarly in the mid 1950s. As such, there is an important issue to be untangled about the close relationship between music and youth cultures/subcultures in this postwar period.

The notion of subcultural resistance in particular remains rife in studies of rock, pop and fan cultures where a bias towards very intense and emotional consumer practices, partly inspired by concept of homology, continues to uncritically receive currency. By contrast, studies of youth music subcultures grounded in ethnographic research methods that at the same time have avoided the excesses of what might be rephrased ‘observer participation’ have suggested that the syntagmatic analysis of subcultural style is an oversimplification of actual young people’s cultural practices.

Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies approach to Music subcultures

Pop music was seen as one of the popular, mass arts embraced by the young generations of the post-war period whilst at the same time the classic arts – classical music included – were in demise. Pop stars reflected ‘a youthful religion of the celebrity’. Teenagers used these popular arts to search for styles that not only afforded surface but also substantial meanings for their subordinate lives. Pop music expressed ‘a strong current of social nonconformity and rebelliousness; the rejection of authority in all its forms, and a hostility towards adult institutions and conventional moral and social customs’. Their account of pop youth culture was importantly one of the first attempts to understand the relationship between young people and mass music media. Its main limitation was to be shared by many that followed it – an assumption that because mass media mirrors attitudes and sentiments which are already there, it is justifiable to read youth subcultural practices from messages contained in music texts.

1980s approach to music subcultures

Accounts of rock and pop youth cultures in the 1980s such as this one by McRobbie began to question the resistance thesis because no noticeable subculture had been conceptualised after punk in the late 1970s. Music as a force for political resistance was displaced to oppressive international regimes such as in the USSR (Street 1986), East Germany (Wicke 1992) and South Africa (Garofalo 1992). The ‘New Romantics’, who emerged as potentially the next subculture, were instead labelled ‘post-punk’. Theorists of British and North American youth cultures became aware that the songs associated with subcultures like punk were as likely to be consumed for pleasure rather than protest.

Music Subcultures examples

The mods, rockers, punks, hippies, hip hop/urban/rappers, emo, indie, hardcore, glam rockers and goths are some examples of music based subcultures. Characteristically, members prided themselves on their musical taste, often dressing to affiliate themselves with similar members, yet also maintaining a sense of individualism within this music subculture. As the Internet dispersed throughout mainstream subculture in the 1990s, so to did the establishment of musical subcultures online, allowing members to communicate freely with one another. Thus weblogs (or blogs) utilised this space, with instant communication devices such as laptops, mobile phones and iPods enabling increased interaction, seeing musical tastes being voiced in this online environment.